- Home

- Corinne Manning

We Had No Rules

We Had No Rules Read online

WE HAD

NO RULES

WE HAD

NO RULES

STORIES

CORINNE MANNING

WE HAD NO RULES

Copyright © 2020 by Corinne Manning

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any part by any means—graphic, electronic, or mechanical—without the prior written permission of the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may use brief excerpts in a review, or in the case of photocopying in Canada, a licence from Access Copyright.

ARSENAL PULP PRESS

Suite 202 – 211 East Georgia St.

Vancouver, BC V6A 1Z6

Canada

arsenalpulp.com

Arsenal Pulp Press acknowledges the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish), and səl̓ilwətaɁɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations, custodians of the traditional, ancestral, and unceded territories where our office is located. We pay respect to their histories, traditions, and continuous living cultures and commit to accountability, respectful relations, and friendship.

This is a work of fiction. Any resemblance of characters to persons either living or deceased is purely coincidental.

The following stories have been previously published:

“The Boy on the Periphery of the World,” Southern Humanities Review, Summer/Fall 2016; “Chewbacca & Clyde,” Vol. 1 Brooklyn, Spring 2014; “Gay Tale,” StoryQuarterly, Winter 2015; “Ninety Days,” Cascadia Magazine, June 2019; “The Painting on Bedford Ave.,” Bellingham Review, Fall 2016; “Professor M,” Moss, Winter 2015 (mosslit.com); “Seeing in the Dark,” Wildness, October 2017; “The Wallaby,” Joyland, August 2017; “We Had No Rules,” Calyx, Spring 2017

The poetry on page 167 is reprinted with permission from Alice Notley.

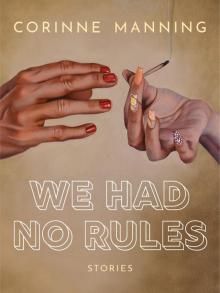

Front cover photograph: Passing the Joint by Amanda Kirkhuff

Cover and text design by Jazmin Welch

Edited by Shirarose Wilensky

Proofread by Alison Strobel

Printed and bound in Canada

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication:

Title: We had no rules / Corinne Manning.

Names: Manning, Corinne, 1983– author.

Description: Short stories.

Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 20190217596 | Canadiana (ebook) 2019021760X | ISBN 9781551527994 (softcover) | ISBN 9781551528007 (HTML)

Classification: LCC PS3613.A356 W44 2020 | DDC 813/.6—dc23

For Ever

“It is this queer I run from. A pain that turns us to quiet surrender. No, surrender is too active a term. There was no fight. Resignation.”

—CHERRÍE MORAGA,

“It Is You, My Sister, Who Must Be Protected,” Loving in the War Years

CONTENTS

we had no rules

gay tale

Professor M

the boy on the periphery of the world

chewbacca and clyde

the appropriate weight

ninety days

the painting on Bedford Ave.

seeing in the dark

the wallaby

the only pain you feel

Acknowledgments

we had

no rules

My family had no rules. At least it felt that way for a time, because most of the rules were vague and unspoken: don’t lie, or steal, or hurt. If I was mean to my sister, or my sister to me, we would apologize. We did the dishes together every night. We shared toys. When she read to me, I would thank her, and if I wanted her to read to me, she would, unless she had too much homework. Our parents’ rules had to be enforced only after we broke them—after my sister broke them. By the time I was old enough to encounter the same dilemma, I already knew the edict, and through watching her, I knew what rules to follow. Which was why, at sixteen, I left home, just as my sister had, only I ran away because there was one rule I couldn’t keep from breaking. If I knew anything about my parents it was where they stood, so why expect different results?

I was lucky, because when it was my turn, Stacy was twentyfour, set up in a rent-controlled apartment in Chelsea with only two roommates. She worked as a paralegal and attended classes at Hunter most nights. It was 1992, and I had a place to go.

Stacy was mad at first. She held my hand as we walked from the subway to her apartment, and I felt so much better now that my hand had a place to be. My hands get icy when I’m nervous. When I was little, Stacy used to rub them until they were warm again, and I wondered if she remembered this. I felt small and untethered as we walked down those streets, because I smelled perfume and trash and urine, saw posters of men kissing and women kissing, and because over the din of cars and voices I heard the roaring immensity of what I’d done.

“You gave them what they wanted,” she said. She jerked my hand as we turned a corner.

I hadn’t seen Stacy since she left, and she’d gone through a complete transformation. She traded running shoes for leather boots that went up to just over her knees and had huge heels. She towered over me by almost a foot. The bangles on her wrists clanked together, and her hair—which was shaved when I last saw her, a rule broken—was a gorgeous orange mess.

She had a unique kind of insight into what I was going through. “You made it easy for them. They want you to feel so ashamed that you leave. There’s this way they pretend there’re no rules, and they subtly suffocate you. That’s what they did to me, only they posed it as a choice. If you wanted to do it differently, you would have given them the ultimatum, like: ‘Either you accept me and we talk about this, or I’m getting the fuck out of here.’”

I pulled my hand out of her grip to adjust my shoulder bag, but I regretted it because afterwards her hand wasn’t available anymore. She shoved it into the pocket of her neon-yellow hunting vest. I stayed close to her, taking as much comfort as I could from the rub of her arm against mine.

We paused at a traffic light and I could tell she wanted to bolt across, but she was trying to set a good example of how to cross the street. I leaned into her a little more.

“I’d rather be with you, though,” I said. “I wanted to be with you.”

It had been a long time since I’d seen her cry, and there was this way that tears just suddenly flooded around her lids—you wouldn’t have known she was upset until this happened—like a mysterious dam had been opened. She grabbed my hand and rubbed her thumb briskly over my skin, then we ran together across the street.

When I arrived at the apartment, there was a closet made up like a room for me and her things were in bins just outside it. I didn’t complain about having no window because she did some sweet things to the closet to make it feel like a room. She suspended a kind of mobile that her roommate Jill made out of spoon and fork handles. Her other roommate, who turned out to always be touring with some band, built a few shelves at the end of the closet so I could put my things up there. My main light was a paper lantern, and sometimes I felt like a caterpillar in a whimsical cocoon.

That first morning she took me to her favourite bakery and watched me eat two chocolate chip banana muffins, mine and hers.

“Look, I’m not going to totally police you, but you can’t just bring home any girl, because you have to remember that this is also home to all of us, and if you and some girl decide to fuck—”

“Stacy!” I looked around to see if anyone had heard, but no one seemed bothered.

“If you decide to fuck, you have to be respectful. No shouting. I don’t want to hear ’cause you’re my baby sister, and Jill’s room is right against that closet and you don’t want to do that to her either. I’ve already told Jill and Toby this, but I’m going to say it to you, too—don’t fuck my roommates. You can have sex with anyone as long as they aren’t l

iving with us at the time. You need to realize this—”

She leaned forward real close and I stopped chewing.

“You and I are partners now, and I worked hard to get this clean, safe apartment with these not-so-clean, stable people, and if you fuck it up, we are both out, and I know you don’t know this yet, but sex is really fucking messy and what you get into will affect me too.”

“I know about sex,” I said.

Stacy smiled, then tried to hide it. “I’m pretty sure all you’ve done is hold hands under the covers at a sleepover and she let you kiss her neck while she pretended to be asleep.”

I looked down and picked up some crumbs from the wax paper with my pointer and put them in my mouth.

“She was definitely awake,” I said.

“I’m gonna take care of you,” she said. “We’re gonna figure out school, and I’ll help you find a job. You won’t go through what I went through. Okay?” She looked at me so seriously.

I nodded. I know that wasn’t enough of an acknowledgment, but the fact that I even nodded is commendable, I think, at sixteen.

I didn’t know, at this point, what she went through. I knew it was terrible, because early on she called my parents and left this message on the answering machine that made me tremble and cry because she was sobbing and saying she wanted to come home. She left a number for a pay phone, and when she answered, her voice sounded like mine, like a child’s, and I begged my mom to get on the phone and listen. And my mom just kept saying, You made your choice, you made your choice, and I heard my sister on the other end screaming, Please, please, the word scraping away, digging for anything decent but striking rock after rock. I hid in the other room until, finally, one of them hung up.

After breakfast, I sat on the toilet lid and watched her get ready for work, just like I used to watch her get ready for school before she left home. She straightened her hair and brushed it out so that it lay smooth and thick around her shoulders. Her lipstick was modestly pink. I didn’t breathe while she applied liquid eyeliner, for fear I’d somehow make her smudge it.

“I’ll be home at two and I don’t have to be in class until seven, so we can do whatever in between.” She smiled at me in the mirror. I was wearing an outfit Mom had picked out for me—red cords and a pink turtleneck.

“Maybe we’ll dress you in some different clothes. I’ll call in some favours.” She closed her eyeliner and dropped it into her purse. She pressed her cheek against mine in lieu of a kiss.

I was entranced: here I was, smelling her makeup again. When she closed the door, I felt a lonely kind of despair.

—

The phone rang—it rang and rang—and I followed the sound to the kitchen. This was my first view of Jill, who sat reading the paper in a tank top and boxers. She was very pale, her hair was dyed black and shaved underneath, and although that made her seem a little tougher than my sister, when she looked up at me, there was something flamboyantly soft about her.

“Don’t answer it, mister,” she said. “We screen.”

A man’s voice snapped on and I jumped.

“Hiii, this is Anthony. I like long messages.” The machine beeped and there was the crackling sound of a phone returning to its cradle.

“Who was that?” I asked.

Jill took a slow sip from her mug. “Anthony. This is his apartment.”

I looked over my shoulder. “Then where is he?”

“He’s dead,” she said, like it was very boring, very common.

She turned the page.

“Oh, okay.” I said. Then: “What from?”

She looked up at me. “The virus.”

It took me a moment to put it together, but when I did I stated: “AIDS,” very loudly, like I’d seen a spider, like the virus was on me. The panic hit me so hard that I would have started crying if I wasn’t so afraid of Jill.

She looked at me with compassion, but her voice was still laced with boredom. “You can’t catch it from living here. It’s transmitted through sharing needles, or through blood or unprotected sex. Want some coffee?”

I didn’t like coffee, but I said sure. She poured it into a cracked teacup with roses on it. She added tons of milk and sugar, then motioned to the seat across from her.

She wore something that smelled like Old Spice—I don’t know whether it was aftershave or deodorant. It could have reminded me of my dad, but it didn’t. I sipped from my little-kid coffee and examined the table. Much of the mail was addressed to Anthony. After a while, I spoke again.

“I’m a girl,” I said.

She squinted at me.

“I just—you called me mister before, so I just wanted to make sure you knew.”

She shut one eye, opened it, and then shut the other. “Of course. Bad habit. Last thing I want to do is fetishize my roommate’s kid sister. ’Tis forbidden.”

“Is today your day off?” I asked.

Her lipstick was so red that even though there was a mark on her coffee cup, there was still plenty on her lips, which she pursed as she folded the paper. “Sure is. If you were me, what would you do with today?”

I crossed and uncrossed my legs. I wasn’t sure how to sit next to her. “I’ve only been to the city twice, and we just rode the Circle Line and had dinner at the Hard Rock Cafe.”

Her face lit up. “Wanna ride the Staten Island Ferry and get a burger?”

“My sister’s home at two.”

“We’ll be back way before then. Can I dress you up?”

—

She undressed in front of me, and when she took off her shirt I looked away. But I didn’t when she was taking off her boxers, because she was talking to me at that point, and I thought she would have panties on underneath, so when I saw her bush—darker and thicker than mine, her furry thighs pinched around it—I pretended like I dropped something and bent down to look for it.

“What did you drop?” she asked.

“A bobby pin I was playing with.”

“I didn’t see anything fall,” she said, and took a step towards me—still bottomless—to help me look for it, I thought, but she put the clothes I was to borrow on the bed, then picked up a sequined dress from the floor and slipped it over her head.

“Found it!” I opened my hand, and then closed it quickly, but she didn’t even look.

She was fiddling with something on her dress, so I stepped into the kitchen to change. From the doorway, I stared at her unmade bed while I pulled on the suit pants. I wondered how many people she had slept with. I put on the Depeche Mode T-shirt and tucked it in.

On cue, she stuck her head around the door frame. “Untucked,” she said, and pulled the front and back out. “Your sister’s like a redwood, but you and I are about the same height. Little shrubs.”

She smiled, just inches from my face, and this was the first time I had to smile at someone who was standing this close to me, whose bush I’d seen, and who I didn’t know very well. She helped me clip on the suspenders, but I wasn’t sure where to let the straps rest—on the outside of my breasts, on the inside? Definitely not on top of them.

“I had a breast reduction,” she said.

I looked at her chest.

“We threw a fundraiser.”

I looked at my reflection in Jill’s mirror. My sister and I had matching breasts, but on me they looked heavy and uncomfortable, which they were. The suspenders made them seem worse.

“Can I just let the suspenders hang down?” I asked. “Absolutely.” Then she pulled on a fur coat splattered with red paint. She told me she found it in the trash like that.

Once we were outside, she slipped her hand in mine. “Is this okay?” she asked.

I nodded.

“It’s just that our outfits look so much better this way.”

—

That afternoon, before she went to class, my sister and I ate pork roll and cheese sandwiches and planned my haircut. I didn’t tell her much about my day with Jill—there wasn’t much to tell, excep

t for the way people looked at us, and how sometimes I wanted to drop Jill’s hand, but she wouldn’t let me. I didn’t mention that I knew about Anthony, but when we were making our food in the kitchen, I didn’t answer the phone when it rang and she said nothing about the message on the answering machine. I told Stacy that I liked the way Jill dressed me, so she added to my wardrobe—an ex’s old combat boots and some more band T-shirts, most of which I hadn’t heard of. She popped one of the records on while we got ready to do my hair. I heard my parents’ voices screaming in the direction of her room: Don’t play music that loud! I winced.

“She sounds angry,” I shouted.

My sister laughed. “She is angry. You’re not angry?”

I shook my head, and she replaced the album with one by another female musician, who sang haltingly over an acoustic guitar but still sounded urgent.

“I like this a lot better,” I said.

“Well, Ani’s pretty angry, too.” Stacy pointed to a picture of her, taped in one corner of the mirror. She had a very pretty shaved skull.

My hair was cut as short as my parents would allow—a rule set in place after my sister—and I kept it pinned back with barrettes. Stacy pulled at a few of the longer pieces, then stepped back. She reached for something in her bag, and I thought it was going to be a pair of scissors, or a picture, but it was a pamphlet. She handed it to me, and I saw that it was for a youth program that promised services I didn’t totally understand, like job placement and training. It was filled with pictures of kids—a bouquet of races—who looked really happy but poor. With some of them I couldn’t tell their gender, and I wondered if any of them had the virus.

“This says it’s for at-risk youth,” I said.

“That’s you. That’s who you are now.”

I looked in the mirror, and I didn’t know if I felt like one, and I wondered if I looked like one. A few of the kids in the picture who looked like girls had shaved heads.

I could hear Jill flipping through some videotapes in the living room. I wanted to get her opinion on my hair—maybe on the youth program, too—but she was staying away while Stacy was around. I wondered if she felt as seriously protective of the apartment as my sister did.

We Had No Rules

We Had No Rules